A New Initiative to Combat Antisemitism in the Publishing Industry

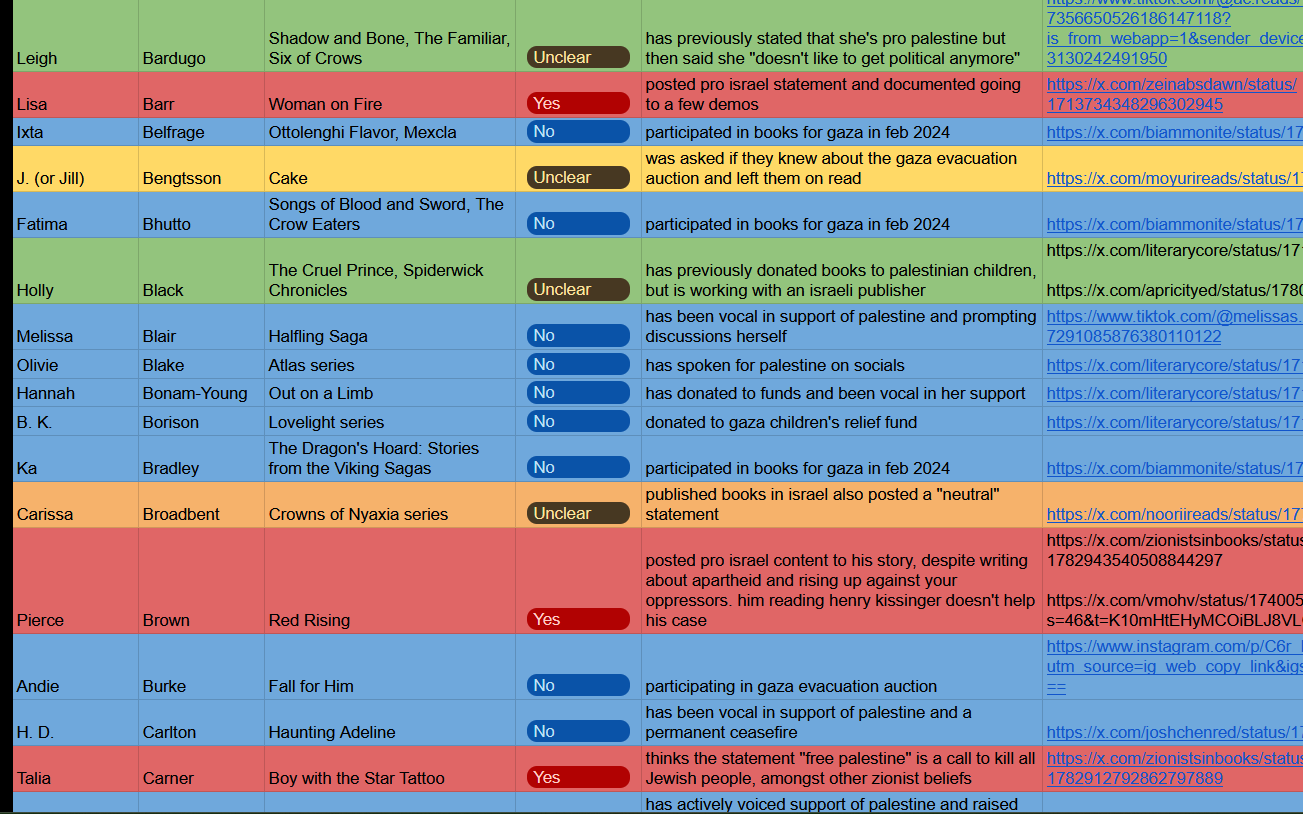

Last year, a list circulated online targeting “Zionist” authors for a boycott. Dozens of blacklisted writers, nearly all Jews, had been condemned for infractions as slight as expressing concern for Jewish friends after the October 7, 2023, Hamas invasion of Israel. The blacklist titled “Is your fav author a Zionist?” came amid a series of other incidents against Jewish authors, some before the start of the war, that together marked a turning point for antisemitism in the publishing industry.

Naomi Firestone-Teeter, the CEO of Jewish Book Council, a New York-based group that supports Jewish literature, described the situation as a series of events that were "one thing after another." She noted that it was like, “Okay, this is bad. This is different. This is different this time.”

The council has launched a series of initiatives to push back against that surge in antisemitism. Its latest, a program called Nu Reads that started in October, aims to bolster Jewish writers, send a message to the publishing industry that Jewish books are valued, and create a community around their work.

Subscribers to Nu Reads pay $154 per year to receive a book by a Jewish writer every other month, and the program has amassed around 500 subscribers. Alongside the books, subscribers will receive a letter from the author, discussion prompts, and extras such as bookmarks and behind-the-scenes content about the writing.

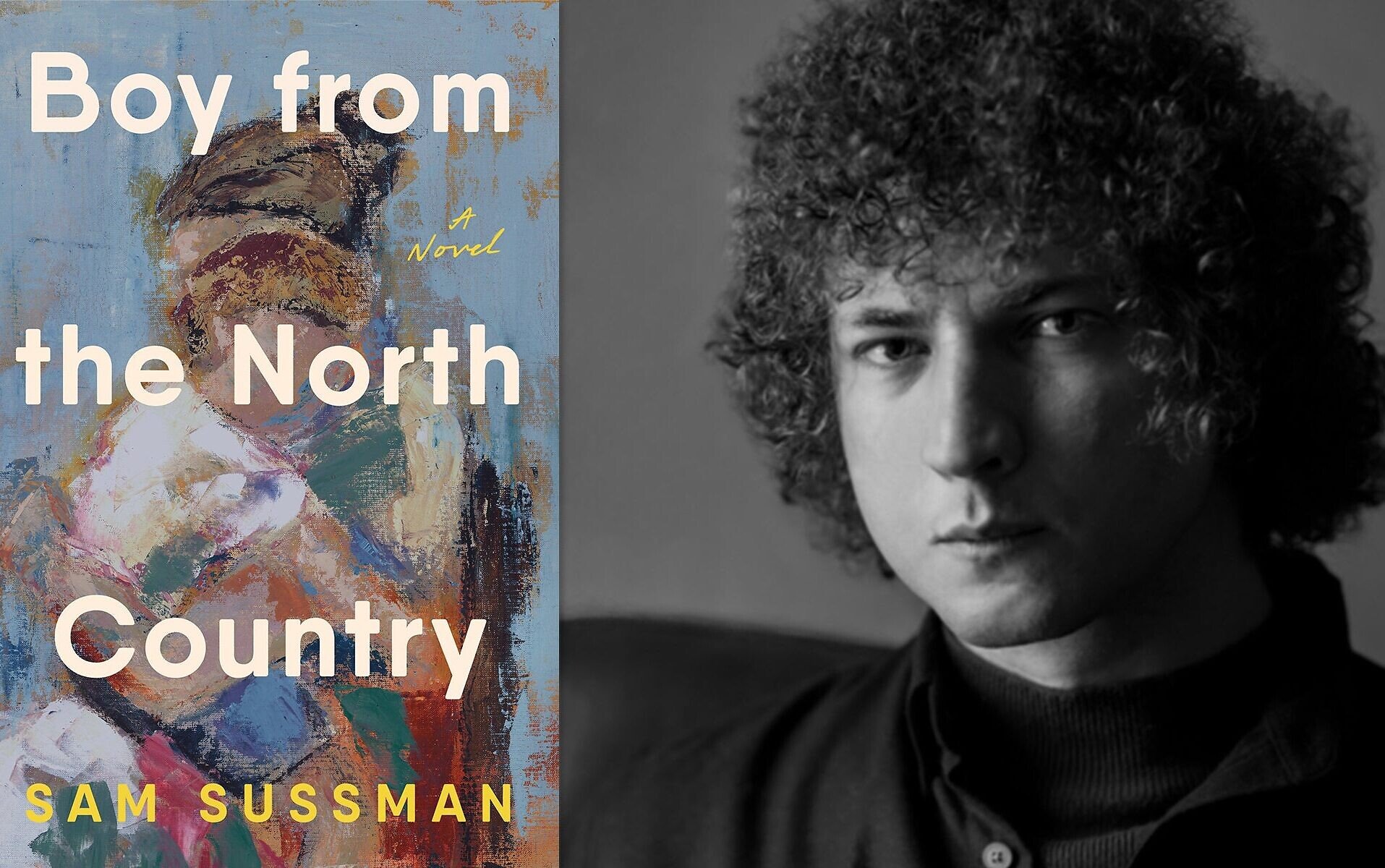

“Judaism offers us so many ways to be in conversation with other Jews,” said Sam Sussman, whose semi-autobiographical novel “Boy from the North Country” was the subscription’s second choice.

“Nu Reads is trying to create a collective reading experience in the Jewish world, and that’s so essential,” he said.

A Reaction from Within the Industry

Firestone-Teeter said that, before the Hamas invasion of Israel, antisemitism had been percolating “below the surface” in the publishing industry. The Jewish Book Council had started hearing that Jewish writers were receiving fewer opportunities to publish in literary journals, for example.

On the morning of October 7, 2023, while the blood was still wet on the ground in southern Israel, Firestone-Teeter, waking up to news of the slaughter, saw an industry peer post on social media, “Resistance is justified. I said what I said.”

“I was like, ‘This is the reaction? This is someone in my industry?'” Firestone-Teeter said.

The book council launched a platform called Witnessing to give Israeli writers an opportunity to be published, and started receiving submissions within a day. Other programs included a hotline for antisemitism in the literary world, workshops on harassment and legal issues, and mental health support groups.

The antisemitic incidents kept piling up, though. The prestigious literary magazine Guernica published an essay by an Israeli peace activist, prompting mass resignations by the magazine’s staff, a retraction, and the resignation of the chief editor. Jewish authors were ostracized, hundreds of authors pledged to boycott Israeli cultural institutions, the writers’ group PEN America canceled its award ceremony due to protests over Gaza, and a Brooklyn bookshop canceled a book launch with the leftist Jewish author Joshua Leifer because the event moderator was a “Zionist.” On Goodreads, the leading online community for readers, Jewish books were “review bombed,” or flooded with negative reviews, and displays at indie bookstores were stacked with anti-Israel literature.

Firestone-Teeter said the Jewish Book Council had started hearing about blacklists around the time of the Hamas attack, but the list that made the news was just the first one to go public. Reports of antisemitism flooded in from authors, publishers, literary students and readers.

“This is definitely the ‘it’ issue of this industry now,” Firestone-Teeter said.

“One of the things that I started saying this past year, when people were like, ‘What can I do? What can I do?’ Was, ‘Buy the books.’ This is a really simple thing. Buying these books matters,” she said.

A Message to the Industry

Amid the turmoil, the Jewish novelist Tova Mirvis, while preparing a book launch, joked to a friend, “I wish there would be a PJ Library for grown-ups,” referring to a program that provides free books to Jewish children.

Mirvis began to take the idea seriously and proposed the program that became Nu Reads to the Jewish Book Council. Like PJ Library, Nu Reads intends to foster Jewish identity, but unlike the children’s program, it requires a payment and aims to send a message to a publishing industry that has become hostile to Zionist Jews.

“We want to demonstrate this is an incredible market. This is a hungry market of readers who are out there who want to support these books,” Firestone-Teeter said. “We hope that message reaches everyone across the industry.”

The program also hopes to bolster Jewish authors who feel stymied by the industry. Firestone-Teeter reported a “chilling effect” for Jewish writing, with authors questioning whether they should rewrite their books by altering Jewish characters or changing Jewish names, and hesitating to submit work to anti-Zionist editors.

Every book matters to an author — writers need their books to reach readers and appear in bookstores to further their careers, and Nu Reads gives Jewish authors an audience, she said.

“The authors see this as a reason to keep going, to keep your Jewish characters in your book, to keep writing on the themes you had intended to write on. We want to give them a morale boost,” she said. “We want to communicate to our community that we need to invest in the books that we care about. We need to invest in the authors we care about and the ideas we care about.”

A Community of Readers

Nu Reads organizers hope the books will foster conversations about Jewish identity and belonging.

“Fiction offers us a way to talk about hard questions,” said Mirvis, who is serving as a writer-in-residence at the Jewish Book Council, helping to shepherd Nu Reads. “It’s a way to really think about people whose experiences are different than our own, but also a way to think about our own experiences in new ways.”

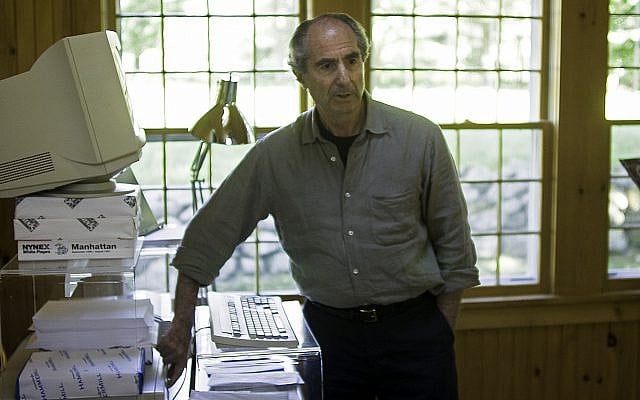

She pointed to an experience she had leading a discussion in her daughter’s high school classroom. The class read Philip Roth’s short story, “Eli, the Fanatic,” about assimilation and Jewish identity.

“What amazed me was, after 20 or 30 minutes, we were not just talking about the story, but people were talking about their own experiences of Jewishness, of identity, of when they feel like they belong, when they feel like they don’t, so I hope that Nu Reads can do something like that,” she said.

Nu Reads organizers will select the books from the hundreds of novels the council receives each year, aiming to present a broad array of Jewish perspectives to readers, with each book tying into the next. There is no “litmus test” when it comes to anti-Zionism or other political issues, Firestone-Teeter said. The books, at the start, will be fiction, and may later include memoirs.

The first book was “Happy New Years,” by the Israeli expat Maya Arad, followed by Sussman’s “Boy from the North Country.”

Arad said positive reviews of her book mentioning Nu Reads had already shown up on Goodreads, including one that said, “I honestly cried so much at the end… OMG did I feel it so much.”

“One of the defining characteristics of Jewish literature is its deep sense of family and community. As a Jewish writer, you are always attuned to your community,” Arad said.

Sussman grew up in rural Upstate New York in a town “far from the conventional American Jewish world” that did not have a synagogue. He connected with that Jewish world by reading Jewish authors like Roth and Tony Kushner.

“For me, so much of what is moving about Judaism is the way that ideas and wisdom are passed from one generation to the next through storytelling. That is our tradition, from the Torah forward, and so reading Jewish literature to me has always been an essential part of my own Judaism,” he said.

“Boy from the North Country” is a semi-autobiographical novel that explores whether Bob Dylan, the singer and Nobel laureate, is the main character’s father, and the main character’s relationship with his mother. Sussman’s mother had a relationship with Dylan decades before Sussman was born, and met him again in the year before his birth. Sussman bears a striking resemblance to Dylan.

The book is partly about what it means to grow up with a Jewish identity, but removed from the larger community, an experience Sussman hopes to communicate to readers.

“That’s not something that other people always understand right away,” he said. “Having a conversation, sharing that perspective through a collective reading experience of one particular book, that’s a way of expanding all of our understanding of what it means to be Jewish.”

The project launch coincides with the 100th anniversary of the Jewish Book Month, a foundational program for the Jewish Book Council.

“We want to create a place of honor in every home for Jewish books, whether you’re starting your Jewish bookshelf or expanding it,” Firestone-Teeter said, adding that, despite industry antisemitism, the project aimed to be “joyful.”

“We all know what an anguishing few years it’s been on so many levels and really in every aspect of our lives,” Mirvis said. “I think what this does is says that there are people who want to read Jewish fiction, who love these books, who want to share them, want to be part of the conversation around them, and really stand behind these writers.”